|

THE HISTORY

OF

ARTIFICIAL EYES

|

|

|

|

|

| |

The eye was a symbol of life to the ancient world, particularly in Egypt, where bronze and precious stone eyes were placed on the deceased. The Romans decorated statues with artificial eyes made of silver. |

|

| Ambrose Paré (1510-1590), a famous French surgeon, was the first to describe the use of artificial eyes to fit an eye socket. These pieces were made of gold and silver, and two types can be distinguished: ekblephara and hypoblephara, intended to be worn in front of or under the eyelids, respectively. A hypoblephara eye was designed to be used above an atrophic eye, as enucleation was not a common practice until the middle of the 1800s. |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

As with most things that evolved over time, it is difficult to trace the inventor of the artificial glass eye, but William Shakespeare (1564-1616) knew of its existence:

Get three glass eyes;

And, like a scurvy politician, seem

To see the things thou dost not.

(King Lear to the Earl of Gloucester, Act IV, Scene 6) |

|

| Enamel prostheses (1820s-1890s) were attractive but were expensive and not very durable. The introduction of cryolite glass, made of arsenic oxide and cyolite from sodium-aluminum fluoride (Na6A2F12), produced a grayish-white color suitable for a prosthetic eye. German craftsmen are credited with this invention in 1835. To make these glass eyes, a tube of glass was heated on one end until the form of a ball was obtained. Various colors of glass were used like paintbrushes to imitate the natural color of the eye. |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

The glass art form flourished in France and Germany where fabricating secrets were handed down from one generation to the next. The town of Lauscha, Germany, had a particularly rich history in both decorative (doll eyes, Christmas ornaments) and prosthetic arts. In the 19th century, German craftsmen (later coined "ocularists") began to tour the United States and other parts of the world, setting up for several days at a time in one city after another where they fabricated eyes and fit them to patients. Eyes were also fitted by mail order. |

|

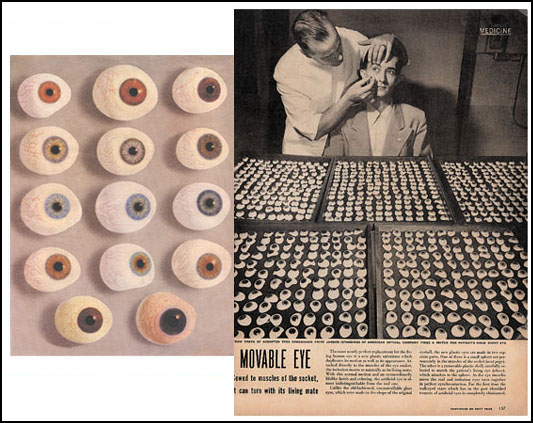

| Stock eyes (or pre-made eyes) were also utilized. An "eye doctor" might keep hundreds of glass stock eyes in cabinets, and would fit patients with the best eye right out of the drawer. |

|

|

|

| |

In the United States, eyes continued to be made of glass until the onset of World War II, when German goods were limited and German glass blowers no longer toured the United States. The United States military, along with a few private practitioners, developed a technique of fabricating prostheses using oil pigments and plastics. Since World War II, plastic has become the preferred material for the artificial eye in the United States. |

|

|

Virginia's History

of

Eye Making

|

| In the early 1800s, most people in Virginia and in the surrounding areas relied on imported, German-made, glass (stock) artificial eyes following surgery. Patients were fit by the local oculist, who was the equivalent of today's ophthalmologist. |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

During the 1850s, several German-founded companies started custom-making prostheses in New York City. Craftsmen sold eyes to regional eye care practitioners, or mailed semi-custom pieces to individuals. For more custom work, an individual needed to travel to New York City or Philadelphia to have a custom prosthesis hand-blown from scratch. |

|

In the 1920s, several of these glass eye companies started to travel to various cities, once a month, to make prostheses for patients. The New York firm of Fried and Kohler, which consisted of brothers, Irwin and Hugo Kohler, traveled to Richmond to work with Salo and Joseph Galeski of Galeski Optical.

Mager and Gougelman (also of New York City) traveled to Norfolk (working with Traylor Optical) and eventually set up satellite offices in Washington, D.C. and Baltimore, Maryland. |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

By the mid-1940s, glass eyes were being replaced by plastic counterparts. In Virginia, this was led by Joseph Galeski (of Richmond, Virginia),although American Optical and several military hospitals started to experiment and dispense plastic artificial eyes. |

|

| Present day ocularistry has evolved through the invention and technique of many individuals. The birth of the American Society of Ocularists (1957) and the refinement of ocular implants and surgical procedures have greatly improved the end results that ocularists can achieve. |

|

|

|

|

Ocular

Implants

|

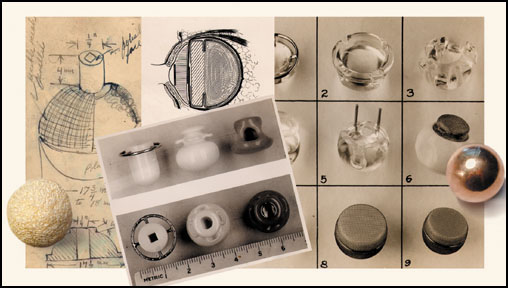

| An ocular implant replaces the lost volume of the natural eye. The first account of placing an implant in the socket, following enucleation, was in 1841. Implants have been made of many different materials, shapes, and types throughout the years. It also helps the artificial eye to have some degree of movement. |

|

|

History

of the

Artificial Eye Clinic

|

Fairfax/ Vienna, Virginia

Michael Hughes relocated from Philadelphia to Northern Virginia in 1991. He absorbed Bill Dubois' practice (of Bethesda) in 1992, and collaborated with Clyde Andrews (of Richmond) starting in 1994. In 1999, Artificial Eye Clinic assumed Langdon Henderlite's practice, servicing the needs of patients in Southwest Virginia and West Virginia.

William F. "Bill" Dubois

William F. "Bill" Dubois 82, who for more than 30 years owned and operated the Contact Lens and Artificial Eye Service in Washington and then Bethesda, died March 26 at his home in Naples, Fla. He had amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, also known as Lou Gehrig's disease.

Mr. Dubois was born in Washington.

He graduated from Montgomery Blair High School in Silver Spring and Washington College in Chestertown, MD. He served in the Army during World War II and the Korean War. He helped develop an artificial plastic eye and later served as the officer in charge of the plastic eye clinic at Walter Reed Army Medical Center.

After leaving the Army in the 1950's, he owned and operated the Contact Lens and Artificial Eye Service until retiring in 1991.

He was a former lieutenant governor of the Maryland Optimist Clubs, president of Manor Country Club and a member of the American Legion post in Boyds. His avocations include golf.

In 1993, he moved from Rockville to Florida.

Survivors include his wife of 52 years, Gwen Dubois of Naples; a daughter, Karen Rhea of Boyds; and two grandsons.

Langdon M. Henderlite

Langdon Henderlite, who was a Richmond native, was born to Langdon M. Henderlite, Ph.D.DD. and Courtney Edmond (Frischkorn) on April 12, 1925. Langdon's father was a missionary, and he spent considerable time in Brazil, South America. Langdon's first visit to Brazil was at age five, and he attended school in both Brazil and in Richmond.

Langdon was hired at Galeski Optical as an apprentice in 1953. Along with Clyde Andrews, Mary Holt and Bob French, Langdon was an important contributor to the infamous "Galeski Eye."

In 1955, to service the needs of Galeski's growing clientele, Langdon was designated the "traveling eye man" for Galeski. A few of his travel points included: Norfolk, Virginia; Roanoke, Virginia; Charlottesville, Virginia, Winston-Salem, North Carolina; Bluefield, West Virginia and Huntington, West Virginia.

The 1950's and 1960's were an incredible changing climate for ocular prostheses. Stock glass prostheses were still being fitted, and the area of western Virginia and West Virginia relied on stock prostheses. The traveling eye man was very welcome to the ophthalmic community in these areas.

Langdon continued to be a significant eye maker in Richmond and the surrounding area, and became a member of the American Society of Ocularists in 1960, three years after its inception. He became board certified in 1980.

With Galeski Optical soon to be sold to a Canadian optical company, Langdon left Galeski Optical and formed his own practice in downtown Roanoke in 1980. He assumed Ludwig Hussar's (the Hungarian dentist) ocular prosthetic practice from Oak Hill, West Virginia in 1981, and briefly collaborated with Pittsburgh and Morgantown, West Virginia ocularist Walter "Bud" Tillman in 1981-82. Langdon continued to work in Roanoke until 1989, when he semi-retired into New Castle, Virginia. His "retirement" came a few years later in 1998 when Michael O. Hughes assumed his practice in southwestern Virginia.

Langdon enjoyed a forty-five year career in the field of making custom ocular prosthetics. He is fondly remembered as "Red" (for his orange-red hair) and for his humor and compassion for those distraught over having lost their eye.

Langdon Henderlite memorium from the 2009 Journal of Ophthalmic Prosthetics

(view PDF)

Presidential Certificate of Achievement from the American Society of Ocularists: Awarded to Clyde Andrews

(view PDF)

My Work as an Eyemaker: The First 55 years

(view PDF)

Clyde Andrews

Journal of Ophthalmic Prosthetics

Fall, 2005

|

|

| |

|

|

|